https://www.pluggedin.com/movie-reviews/worth-2020/

In our day-to-day evangelistic activities at K180, we distribute countless quantities of Christian literature - from Bibles to Gospel flyers. One such flyer, entitled “How Much Are You Worth?”, often proves to be the most challenging for those whom we engage with in conversation, out on the streets. As I’ve drawn countless peoples’ attention to this question, reactions have varied widely. “I’m not worth much at all”, said one man. “I’m worth 1 million pounds”, said another. Others have stood before me stunned and unsure of how to respond altogether.

The links between every response that I’ve ever heard, however, is simple: nobody can ever answer that question swiftly, without hesitation, and asking “worth in terms of what?”. Granted, it’s an abstract and difficult question that many people have apparently never considered for themselves. But it is difficult precisely because one cannot successfully measure their self-worth through worldly constructs such as financial wealth, or relationships. For if wealth or relationships bring worth to our lives, what happens when we find ourselves destitute or alone?

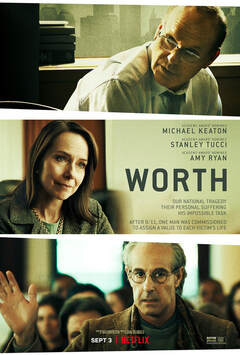

Discovering the futility of such measures by which we determine our self-worth, from a philosophical and spiritual standpoint, could leave us devastated and frantically searching everywhere for validation. But what if we dare ask ourselves, “How much am I worth to God?”, would that change one’s outlook on humanity’s self-worth, as we acknowledge our creator God as the one who “knit me together in my mother’s womb (and you in your mother’s)”, and sent His only son Jesus Christ to die for us that we may live? In my heart, I know it would. But specifically, in regard to Worth, what if Kenneth Feinberg – an American attorney who headed up the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund – asked that question not only of himself, but also the victims of 9/11, when determining the monetary value of those who perished? I’d like to think that Feinberg might have learnt that he was calculating the incalculable. And to some extent (as depicted in the film), he does. We watch as Feinberg moves beyond distancing himself from the grief-stricken victims’ families, to come to see them and their loved ones as real people – not numbers – who were valued beyond all the money in the world. And so then, everybody counts for something. But what exactly is that something?

And so, alongside his team, Feinberg then determines that each family’s pay-out should be calculated by their loved one’s income, generated from their positions within the companies affected – ranging from caretakers to high-ranking financiers. Without realising the case may require more of a personal touch, Feinberg presents the fund and its rules to the families in an impersonal manner. But in their grief and anger they turn on him. Many of them despair at the thought that the life of a “pencil-pusher” in the financial sector might be considered worth more than that of their loved ones, who cleaned and served food in the towers, or died trying to save others. The group of the victim’s families agree unanimously: the fund is broken, and the compensation offered by Feinberg’s team isn’t nearly enough to support those left behind.

It's in these emotionally raw moments that Feinberg first encounters the difficulty and insensitivity of attempting to determine one’s monetary worth. He’s conflicted. Even a desire to serve his country in their time of need, doesn’t negate the fact that he is doing a disservice to those whom he is serving. It’s only when Feinberg and the team begin to meet with the victim’s families personally, that they begin to understand that a one-size-fits-all pay-out is not only dishonouring to them, but completely insufficient for many of the families who live on the breadline. So, they spend time getting to know the families and their backgrounds, listening to stories about their loved ones, to help determine how much they may need to get by or what might be considered a ‘fair’ amount of money, given the circumstances. But even after the fund awarded $7 billion to its applicants, and Feinberg (alongside his team) is revealed to have helped countless grieving families, we’re still faced with a poignant realisation: this money will never be enough to heal the wounds of losing someone who will be worth more to their families, than Feinberg – or anyone else – will ever know.

He loves us more than anyone else ever could because he paid the highest price imaginable: sending His one and only Son Jesus to die for you and for me, so that we may be saved. God decided that we’re worth the death of Jesus, even though we’ve turned our backs on Him and done so much wrong against Him (Romans 3:23). We deserve to make the payment for our sin (which is eternal separation from God), but God chose Jesus to take our punishment upon himself by dying upon the Cross, so that we may have the debt wiped away: “For God so loved the world that He gave His one and only Son, that whoever believes in Him shall not perish but have eternal life” (John 3:16, NIV). But Jesus didn’t remain dead, because God “…raised him back to life” (Acts 2:24, NLT) so that through his death on the cross & resurrection, we might “have life… and have it to the full” in friendship with Him now, and in Heaven for all eternity. If we choose to accept Him into our lives today, turn from our sin and receive His forgiveness, it’s only then that we can begin to understand our infinite worth in Him – the One who paid the highest price imaginable for us, loves us with an everlasting love and is willing to forgive us of all sin. Outside of Him, we can never be worth as much as we are to God. Contrary to what Feinberg and the filmmakers may think, our worth and value is not dependent upon external factors. If we are found in Jesus, we have infinite self-worth which we can rely on and that will never let us down.

Challenge:

Why not prayerfully invite a friend or family member who doesn’t yet know Jesus, to watch Worth for themselves? Use the film’s themes to ask them what they thought of the film, if they spotted any links to Christianity and what they might think of the Gospel’s response to this subject.

If you feel able to, ask them how they would have approached the task at hand if they were in Feinberg’s position. Would they have stuck to the formula, or gone down a more personal route to determine someone’s financial worth? Regardless of their answer, ask them why. Afterwards, prompt them to consider how they might determine how much they’re worth. Are there any methods they’d use to measure it?

Take the opportunity to share the hope of the Gospel message with them, encouraging them in the knowledge that we are worth so much to God. Explain that we’re important to Him, and we know this because He made us with love and care (Psalm 139:13, Jeremiah 1:5). He also watches over us no matter where we are, which also indicates how precious we are to Him (Psalm 139:1-3). But be sure to explain that our worth is most evident in Christ, who gave His life for humanity, so that we might live with our heavenly Father for eternity. Ask them if they have ever considered their worth to God, and if they’d like to explore for themselves.

Prior to watching the film for yourself, however, take a moment to pray that God would speak to you through the show. If you feel comfortable, pray this prayer over all your future, film-watching experiences:

Dear Lord, as I watch this film, I ask that you would be present here with me. Highlight to me anything within it that is honourable, anything that can be used in conversation for your Kingdom purposes. Amen.

Worth is currently available to stream on Netflix (U.K.)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed