Please note: The following text contains spoilers. Viewer discretion is also advised – this film is rated ‘12’. For more details on the film’s content, read Focus On The Family’s Plugged In Review: The Terminal.

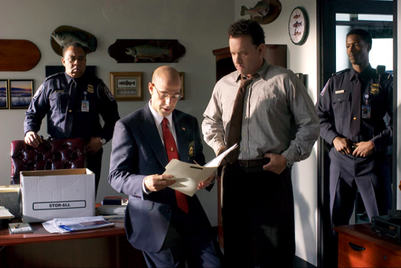

Frank Dixon: “…you don't qualify for asylum, refugee status, temporary protective status, humanitarian parole, non-immigration work travel visa… You at this time are simply…"unacceptable".”

To this day, I continue to maintain that Steven Spielberg’s The Terminal is a Christmas film. Am I able to provide evidence to substantiate my claim? To some extent, yes – even in spite of the film not being explicitly set at Christmas. When commenting upon the reoccurring themes of director Frank Capra’s critically lauded filmography, film author Richard Griffith summarised them thusly: A “messianic innocent ... pits himself against the forces of entrenched greed. His inexperience defeats him strategically, but his gallant integrity in the face of temptation calls for the goodwill of the "little people", and through their combined protest, he triumphs”. Such motifs are present within Capra’s It's a Wonderful Life (1946) and have continued to influence generations of Christmas films after it – from the heart-warming, to the unapologetically whimsical. The Terminal is the collective embodiment of Capra’s favourite subjects, lovingly wrapped up in the spirit of the Christmas season. But it serves a greater purpose to us today, in bringing us far more than festive cheer, but a timely message with strong links to the hope of the Gospel message.

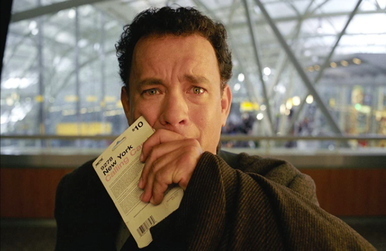

Previous to writing this article, my recollection of The Terminal largely consisted of Hanks’ Victor acting non-plussed for the majority of the film’s runtime. And to some extent, I’m not wrong. Spielberg and his screenwriters know how to write Victor, a fish out of water, into some highly amusing situations – not least when an unassuming passenger asks Victor with a heavy sigh, “Do you ever feel like you’re living in an airport?”. However, I forgot just how much pathos Hanks imbues within the character, particularly in a scene in which Victor realises that his (fictional) nation of Krakozhia is at civil war. Victor, a non-English speaker, cannot understand the news reports he sees on the terminal’s televisions, and when he tearfully begs passers-by to help translate for him, he is only ever brushed aside. To make matters worse, customs officer Frank labels Victor’s visa status “unacceptable”, but we can’t help but feel in the moment, that by Frank’s actions and attitudes, he finds Victor to be just that. These scenes are emotional, not least because they resonate with audiences in 2020, when the plight of refugees is such a disturbing reality. Of course, this is a more sanitised version of so many refugee stories, but there is something so genuinely painful about Victor’s struggle. For the most part, we forget that we’re watching Tom Hanks and instead see a man who is stateless, robbed of his identity and scared.

In turn, Victor’s refugee story unexpectedly brought to mind the plight of the Israelites, who suffered oppression due to their enslavement within Egypt. Foreigners in a far-off land, the Israelites were treated cruelly as refugees – forced to work as captives in a land they could never call home. Whilst Victor is never enslaved throughout the course of the film (he is inadvertently employed at one point, however), he is oppressed. Those who work within the terminal’s shops insult, laugh or ignore him, either because they don’t take the time to understand Victor, or they’re just ‘too busy’ to acknowledge him as someone who requires basic human rights. Frank’s actions are far worse, however. Throughout the course of the film, he uses condescending language/tone, gives Victor insufficient supplies and makes it his personal vendetta to rid the terminal of Victor, without once trying to understand him. In Exodus 23:9 (NLT), God specifically instructs his people, the Israelites, not to conduct themselves in this way: “You must not oppress foreigners. You know what it’s like to be a foreigner, for you yourselves were once foreigners in the land of Egypt.” Following Him liberating the Israelites from their captivity, it was God’s desire for the Israelite people to live their lives as He does, imitating His holy behaviour in every way. They were to be a people whose righteousness clearly set them apart from the evil practices of their time, and ultimately spoke to the righteous way in which God acts – generally and towards humanity.

Rather than treat them as outcasts, therefore, God called for the Israelites to treat foreigners or refugees as citizens among them, and to do so with love. In fact, they were instructed to: “Treat them as you would an Israelite, and love them as you love yourselves. Remember that you were once foreigners in the land of Egypt. I am the Lord your God.” (Leviticus 19:34, GNT). But God’s desired treatment of foreigners and refugees went further than that, when God commanded the Israelites to Invite them to be a part of their community. Living by God’s holy Law meant that foreigners were to be included in all aspects of the Jewish community, including provisions for them to be treated equally under the law and to even be included in festivals and celebrations of the community (Deuteronomy 14:28-29, 16:14, 26:11).

So, when we choose to no longer live as foreigners and strangers to God, and come into friendship with Him, He welcomes us into relationship – a perfect friendship which saves us from eternal death in Hell and gives us the gift of eternal life spent in Heaven with Him (“For “everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.””, Romans 10:13 – ESV). When we put our faith in him, we become part of God’s community. You are “…not foreigners or strangers any longer; you are now citizens together with God's people and members of the family of God.” (Ephesians 2:19, GNT). Such wonderful truths encourage me, as a Christian, in the knowledge that I can and should identify with the idea of not belonging, as the reason why I treat refugees or displaced people without discrimination. For in His perfect, loving kindness, God did not ignore me or my fellow Christians, even though I had done wrong in His eyes. So, we too must share that same kindness with others today.

Why not prayerfully invite a friend or family member who doesn’t yet know Jesus, to watch The Terminal for themselves? Use the film’s themes to ask them what they thought of the film, if they spotted any links to Christianity and what they might think of the Gospel’s response to this subject.

If you feel able to, ask them what they think about Victor and his mistreatment by those within the terminal. How does that make you feel as someone who might have missed the foreigner/stranger in need? Prompt them to consider the characters’ lack of compassion – how would they respond to the situation if they worked in the terminal? Later, if they're open to hearing it, take an opportunity to share the hope of the Gospel message with them, mentioning the fact that Victor was eventually shown unconditional kindness, despite the terminal and America, not being his home. To end, share with them about the unconditional love and forgiveness that is found in a relationship with Christ.

Prior to watching the film for yourself, however, take a moment to pray that God would speak to you through the film. If you feel comfortable, pray this prayer over all of your future, film-watching experiences:

Dear Lord, as I watch this film, I ask that you would be present here with me. Highlight to me anything within it that is honourable, anything that can be used in conversation for your Kingdom purposes. Amen.

The Terminal is available to stream on Netflix (UK).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed